Triumph Daytona

British bikes in the rain. What could be more appropriate?

The new Triumph Daytona is unabashedly a street bike. It is not a race replica if for no more reason than there is no race bike for it to replicate.

Street bikes, as I have opined before, are more about character than about capability. Like with other extroverted fashion displays, motorcycles answer the question “I am the kind of person that rides a {insert name of brand here}” What Ford and GM learned early on (with Honda and Yamaha to follow later) is that brands are often too broad and that, to really give people the opportunity to micro express themselves through their transportation decision, they needed to subdivide their brands into smaller units. The guy with the Acura doesn’t want to think about his Honda. The guy with the R1 doesn’t want to be associated with the Royal Star.

I say “Ducati” and an image springs to mind. That image has been carefully formed by Italian craftsman, and much of that image was formed in just the last fifteen years. Most enthusiasts can describe the typical buyer of Ducati. However, I say “Triumph” and nobody knows what to think. I don’t know what to think.

Of course there is the whole Bonneville thing, and the Speed Triple (and the painful racing stories documented by James Lickwar) but how do you reconcile the Bonneville (a retro throwback) with the TT600 and the Daytona? It is hard to form a concrete picture of what it means to arrive at the local hang on a Triumph. And do you have to wear that greasy waxed cotton and put union jack flags on everything?

Due to Roadracing World’s hardcore moto-aficionado readership we are usually only invited to review hardcore racing or sporting motorcycles. The American representation at the press launch events is usually the same group of writers from the same group of motorcycle enthusiast magazines. The Triumph launch only included editors from four US bike magazines, and two additional writers from general consumer magazines widely read by men.

Investigating this violation of press launch protocol confirmed what had only been suspicion. Triumph is aiming for the born again biker in their late thirties to late forties with their new Daytona. Someone who has been out of the motorcycle market for awhile. Someone that doesn’t care about top speed or maximum lean angles but wants to hear about CNC combustion chambers and old world craftmanship.

There is no point in comparing the Triumph to the race replicas from Japan. From a pure performance standpoint, the others are better. Off the track, of course, that becomes a moot point. Due to inclement weather and the Portugese traffic safety record, we only rode on a track. Time constraints and the aforementioned inclement weather restricted the riding impression to slipping and sliding around a cold and sloggy GP track (and they say a tie game is like kissing your sister) and a single session on a dryish, dry like, dryesque track.

Frustrating conditions to evaluate a motorcycle but enough to determine that, for their intended target audience, Triumph has built a much better bike than they had to. The Triumph only Showa suspension adjusts, the Triumph badged Nissan brakes brake, and the three cylinder 955cc engine puts out more than enough power to make your average born again biker reconsidering his decision to buy the top end model. The styling is sporty and refined without ripping off too much from the Italians or the Japanese. The paint schemes are tasteful and refined. The engineering is solid and the details will provide long hours of enjoyment to owners who can point out the cast, flowed collector in the stainless steel exhaust pipe (“That’s F1 technology right there that is”), the braided steel brake lines and the 90 degree valve stems in the forged aluminum wheels.

Triumph understands the motorcyclist’s need for accessories and has provided a reasonable selection straight from their own catalog. The bike I rode had the optional loud muffler, the appropriate remapped fuel injection (which does not require a secondary box to accomplish this trick) and a passenger seat replacement cowling.

The 120 degree triple, not surprisingly, has an exhaust note that is somewhere between a four and a twin. Each single power pulse has a nice solid punch like a twin but at higher RPM it takes on more of the multi-cylinder howl as opposed to the twin’s squawk. It is a very pleasing sound. Compression braking is similar in its compromise. Less than a twin, but more than a four. In the wet slippery conditions it was all too easy to have the back end sliding lazily back and forth on the downshifts.

The power delivery, again, is unique to the triple. There is plenty of low end grunt which gets the front wheel light (or up) exiting corners and while shifting through the lower gears and, while not feeling flat on the top (like a twin) it lacked the sort of high RPM rush that is so endearing with four cylinder bikes.

Compared to the slick delivery of power delivered by Italian and Suzuki fuel injection the Triumph has a bit of sorting out to do. Riding through the tight turns of Estoril in the pouring rain I wanted precise throttle control. I wanted to be able to keep a slight positive throttle so as not to load up the front tire while still being able to make steering corrections (since I was lost) and control the rear wheel spin. However, it was very difficult to find a partial to positive throttle position. Slightly opening the throttle produced too much acceleration but easing of the throttle resulted in a huge drop in power, over steer and front wheel sliding. At a faster pace and with more traction it was less of an issue but, like with the TT 600, that sort of throttle response will be difficult and intimidating to the less experienced rider.

Although light in an absolute sense, the Daytona is a tad hefty for a sport bike. The steering geometry is engineered to compensate for this and still provide light and fast steering. The weight was the most noticeable through the slowest turn with the fastest transitions but the steering was fast enough (traction willing) to allow me to throw my weight from one side of the bike to the other and make the fast transitions without having to: A. Really muscle it or B. Run wide over the curbs. Through the fast turns (again, traction willing) the bike was reasonably planted, precise and secure.

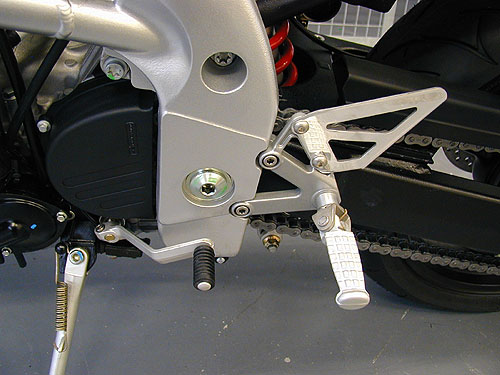

The riding position was just about perfect for a road going sport bike with just the slightest complaint about the footpegs being ever so slightly too far forward. The bars were low enough to get weight on the front wheel but high enough to prevent wrist aches. The reach to the bars was natural and the narrow tank was unintrusive to both riding in a straight line and cornering gymnastics. The fairing provided an ample bubble for the front straight and the seat seemed reasonably comfy.

A slippery footpeg and a non-reversible shift lever say street bike.

The mysterious bushing at the base of the footpad remains a mystery.

Triumph transmissions have always been a bit of a soft spot. The transmission felt okay most of the time but it required a firm positive input on the downshifts and one had to decidedly close the throttle to make the clutchless speed shift stick. I amused the onlookers on the front straight one lap by failing in my attempts to shift into fourth gear in three attempts. By paying more attention and not rushing I was able to avoid future episodes but others reported similar problems.

The brakes are Nissan units and provide typically responsive power. The brakes worked very well on the track and the stock stainless steel lines offered a nice tight lever. One dynamic I noticed was that the brakes, like on a race bike, would get really spongy sitting in the pits after being used on the track. The soft feeling goes away after the first lap or two and the brakes seemed as good or better than anything coming out of Japan right now.

Without any dry track time I never got a chance to play with suspension settings on the track. With a few hours to kill in the garage I found ample opportunity to play junior suspension engineer. The Showa built shock and forks seem to be of very high quality and have adjustment ranges that are usable. I was trying to tune the shock of my friend’s new GSXR 750 only to find an inadequate capacity for rebound damping. The Showa on the Triumph has no such problem. Full rebound and the shock will barely move. About one full turn out seemed right. Granted that on the track I never got a chance to really test the suspension (and Estoril is so silky smooth that I would have been hard pressed to find an bump to run across) but, as far as I could tell, the suspension felt great.

Overall the bike was another pleasant surprise from Triumph. Performance enthusiasts that want a sporting exotic without the maintenance headaches of the Italians or the performance deficit of the Germans might want to trot down to their local Triumph dealer. And, if our hypothetical performance enthusiast is willing to use a high percentage of the bikes capability, his friend’s on other sportbikes won’t be able to meet his eye after the their next collective track day.

Under the Bonnet

Triumph introduced the Daytona in 1997. It had a tube aluminum frame, a three cylindered motor, a single sided swingarm and styling that had not quite made it out of the early nineties. It was billed to be a revolutionary bike from Triumph since it was the first bike they had made in modern times that was not built in the modular model. It never quite lived up to it’s press that it would compete head to head with the Japanese.

The new one is significantly better handling, looking and running. It still doesn’t compete with the best of the super sport bikes but I don’t think it has too. It is already overkill for virtually all street riding.

In order to make the bike better, faster, stronger Triumph tweaked most of the systems on the bike to achieve better results.

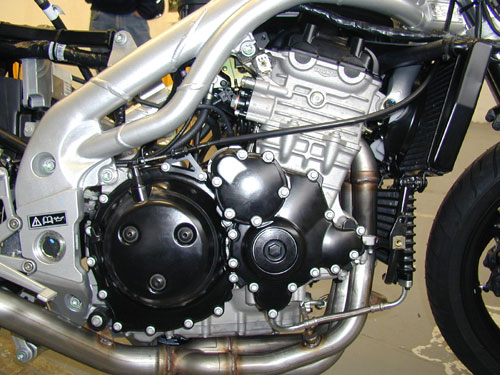

The three cylinder engine received a new head design with a radically tighter included valve angle. The intake valves were make 1mm larger while the exhaust valves were made 1mm smaller. The combustion chambers and ports are CNC machined for perfect symmetry between cylinders. The pistons are forged and the lighter connecting rods are carburized, both for strength while the compression ratio is boosted from 11.2 to 12:1. The redline has been raised to 11,000rpm (from 10,500) and the engine bearings have been narrowed to reduce friction. The counter balance shaft is retained and sits in front of the crankshaft in the front of the engine.

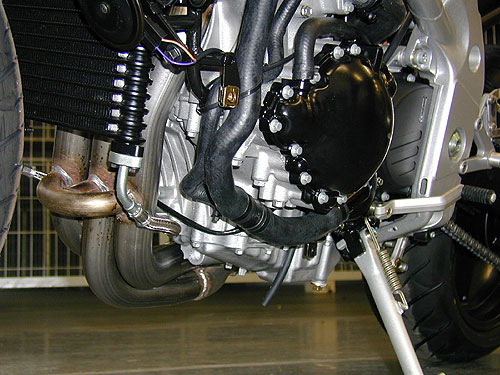

Detail of the heavy duty plumbing and balance pipe in the exhaust.

The airbox does not yet feature any sort of ducting to the fairing so much work was done in an attempt to minimize the amount of engine heat getting into the airbox. Hot air in the airbox is the principal cause of the off idle dip in power after sitting at a stoplight in the summer. The cooling system has received two upgrades. Jets of oil now cool the pistons which are then in turn cooled by a large air cooled oil cooler. Air Cooled oil coolers are more efficient but are heavier. The coolant radiator now uses a thinner core to increase it’s efficiency without adding weight. Triumph typically seems to run pretty hot. This one was no exception. Triumph has tried to shield the rider from some of that heat by adding ducts to the fairing to keep fresh air blowing on the rider’s legs and on the frame.

The fuel injection sports 46mm high-pressure die cast throttle bodies and smaller, lighter injectors. The stainless steel exhaust pipe has unusual cast pieces at the head and the collector. Apparent this was done to improve flow and performance. The exhaust pipe also has a pricey lambda sensor that monitors the fuel mixture from between 1,000 –4,000 rpm to further improve low speed response.

One of the few bikes that would loose significant weight from an aluminum bolt kit.

Note the Lambda sensor in the header pipe.

The engine covers are internally webbed to damp sound and are secured to the motor with many, many bolts.

One of the things you don’t see on the Triumph motor is a three piece crankcases which would have allowed them to stack the engine shafts and build a shorter motor and therefore, shorten the wheelbase while retaining a long, bump smoothing, swingarm.

The chassis has seen multiple improvements.

The single sided swingarm was dropped in favor of something stronger and lighter. Wheel base on the chassis is reduced by 14mm to 1417mm largely through the new swingarm. Rake is changed to an extremely steep 22.8 (from 24) and trail is down 5mm to 81mm. The rear of the bike now sits higher which, of course, further speeds the steering while improving ground clearance. The rear tire was reduced from a 190 to a 180 which also make the bike steer with less effort.

The rear shock is now aluminum bodied and seemed to offer a wide and appropriate range of adjustment. The forks are now valved slightly softer but still seemed to be in the ball park.

The front wheel is from the TT600 is of forged aluminum which is both strong and 450 grams lighter than the hoop it replaces. The front rotors have lost one mounting bolt down to five) but still ride on ten buttons. The brake rotors are also the thinnest I have seen on a sporting motorcycle at 3.5mm. We used to taco 4.0mm rotors but Triumph claims they have no such problems.

Tasteful fender mounts on custom Showa forks with Triumphed badged Nissin calipers

grabbing the thinnest disks around bolted to a very lightweight forged aluminum wheel.

New plastic technology allows the lovely bodywork (in Caspian Blue or Aluminum Silver, I liked the silver one best) to be made thinner while retaining the original strength. A new headlight (which I also found to be very tasteful) graces the pointy end. The gas tank feels narrow on the bike but holds a generous 21 liters (most bikes hold about 18l).

The bike is supposed to produce 147 bhp at the crank (which is about what an R1 is supposed to make remember) and weighs in at 188 kgs dry.

There are lots of factory accessories available directly from Triumph including loud mufflers, a luggage rack, tank bag, saddle bags, an alarm and assorted other bits.

Compromise is a difficult balance to engineer. The Triumph successfully walks the line between street and track, and sport and sport touring. It is more exclusive than the Japanese offering, more livable than the Italians and more sporting than the Germans.