Existentialism and Smokestack Industry in Nippon

Kawasaki Media Tour

Japan

May 22–29

Wild Card Editor’s Note-

National politics are both sport and livelihood for the residents of Washington, D.C. Periodically we have elections but since most of the residents of the country are either ignorant (vote on bad information) or apathetic (don’t vote) few career politicians are ever displaced from their offices for their actions. This allows politicians to vote based on their donor base interests and not on their constituent’s interests. Periodically the sheer shamelessness of the process is exposed in the more egregious cases (see: Abramoff, DeLay, Jefferson) but for the most part your country is run by professional lobbyist trading campaign money for favors.

Although there are a few toothless laws that regulate the activities, one of the time honored activities is known as the “junket”. Junkets are often called “fact finding” trips which involve a fair amount of golf in exotic locations.

Perhaps more insidious to the apathetic and listless American public is the “Movie Junket” where film critics are selectively vetted by studios in return for favorable reviews of the films. I mean, it's one thing if your elected representatives decide to forego oversight of the country’s food, energy, water, banking, healthcare, credit cards or real estate but what if you waste 90 minutes seeing ‘Driven’ because some guy got a plane ticket and hotel room to come see the movie?

In the enthusiast press this can be even more insidious. Many magazines are owned by large corporations that depend on massive amounts of advertising dollars to make their numbers. Subscribers do not buy advertisements and researching articles costs a lot of money so the logical business move is to use manufacture money to provide content (trips, bike reviews, press launches,etc) all in such a manner so as not to offend the same companies in order to keep the flow of advertising dollars flowing.

All those bike reviews I write for the magazine are mostly based on press launches where all expenses (sometime lavish, sometimes basic) have been covered by the manufacturer. At least in those circumstances my mission is a little more straightforward. I show up, I ride the bike, get some pictures, try, to the best of my abilities, to convey what the bike is like, and then leave it to the comparison tests to sort out the relative ranking. As a bonus, I know that if I write something that is off message for the manufacturer it is Editor Ulrich who will have to face the irate delegation from the OEM and not me; a moment of schadenfreude in its own right.

In the past fifteen years of writing for RW I have only been on two straight junkets. The first was a Japan goodwill tour by Honda and now, a second by Kawasaki. These trips do offer an opportunity to learn, research and write in more depth than a simple press launch but if you see a lot of coverage about Kawasaki the company and many of the same pictures (for the most part we were not allowed use of our own cameras) appearing in multiple magazines and websites over the next couple months.

With that conscience assuaging disclosure I can now relate some of what I learned about Kawasaki Heavy Industries limited.

– SPQF

(Photos by SPQF unless otherwise noted)

Kawasaki was founded in 1878 by Shozo Kawasaki. Apparently Shozo had started his professional career in the shipping industry and switched focus from shipping to ship building after a storm sank his cargo ship. Initial funding of the business was assisted by then Finance Minister of Japan (who later became the Prime Minster of Japan) Masayoshi Matsukata. The term “Japan inc” is sometime used to describe the unified efforts of the Japanese government, corporations, banks and, sotto voce, the Yakuza (organized crime). Matsukata was very influential in creating the financial structures of Japan and Kawasaki is, arguably, one of the very first “Japan inc” entities.

The keystone from the original Kawasaki building bearing the original logo

for Kawasaki; an adaptation of the Chinese symbol for ‘river’.

Matsukata’s son Kojiro became the president of Kawasaki in 1896 and, fueled by fat government contracts, expanded the company tremendously over the course of the next twenty years.

Originally established with two shipyards all the Kawasaki ship building capacity was centralized in Kobe in 1886. Kawasaki was one of the first Japanese ship yards to adopt western shipbuilding architecture and construction techniques using western technology including a massive German gantry crane in 1912 to assist in the construction of the battle cruiser Haruna (which, thirty years later, would be shelling Henderson Field in Guadacanal).

In 1906 Kawasaki branched into building rolling stock (train locomotives and train cars) to provide a broader base of customers beyond ships. The demand for steel for both rail cars and ship building was such that Kawasaki vertically integrated by starting a steel company. 1906 also saw Kawasaki’s first steam turbine engine.

In 1918 Matsukata started the Kawasaki airplane division producing Japan’s first metal airplane. Matsukata even took the company full circle by opening a Kawasaki branded shipping company in 1919. With the expertise in steel production, steel construction and government contract procurement Kawasaki began building massive steel highway bridges in 1923. With a dabble in personal transportation in 1933 Matsukata had basically laid the foundation for virtually all of Kawasaki’s modern business lines: Ships, steel, rail cars, turbine engines, aircraft, marine engines and personal transportation.

Kawasaki built the bridge supports.

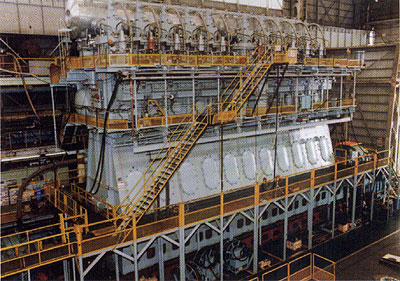

A model of an older diesel marine engine. Note man in lower left hand

corner for scale. The new engines are of a different design but of similar scale.

The Akashi works, home of most of Kawasaki’s modern motorcycle production, was originally founded in 1940 as an aircraft factory to make war planes for World War II notably the Hien fighter. As part of the Japanese military industrial complex much of Kawasaki’s production infrastructure was targeted and destroyed by allied air raids in WWII.

A Kawasaki aircraft carrier model from their museum. Apparently two large

luxury passenger liners were ordered in 1939 and then redesigned

to become aircraft carriers part way through their construction.

Although the infrastructure was damaged Kawasaki survived the war with its engineering capacity relatively intact and quickly established connections with US companies. By 1952 Kawasaki was building helicopters in association with Bell. With the demand for aluminum fighter aircraft substantially reduced Kawasaki began using Akashi to manufacture motorcycle engines in 1953 followed quickly by the production of complete Kawasaki branded motorbikes.

The steam turbines of 1906 became gas turbines (power generation, marine and jet aircraft), the ship building expanded to build massive tankers, bulk carriers and container ships, the trains became everything from the high speed (180mph) Shinkansen trains to the New York City subway cars and the small engines became the basis for their motorcycles, watercraft and other consumer products.

A cutaway of a gas turbine engine.

Beyond the core foundation work laid by Matsukata, Kawasaki also expanded into industrial robots, aerospace and complete turnkey industrial plants. These plants include such things as a fertilizer plant for Iran (fertilizer huh?), power plants, cement plants and mining operations. Kawasaki even built the boring machines that dug the tunnel between England and France.

This is a model of the rig used to cut the Chunnel between France and

England under the English Channel. In the center of the picture you can

see the internal cat walks. The original was about sixty feet in diameter.

Kawasaki’s production plants in the US include trains, robots and motorcycles in Lincoln Nebraska and a smaller plant in Yonkers, NY.

Kawasaki has a long history of manufacturing and engineering in a wide array of fields well beyond Ninja 600s. After touring the ship yard and rolling stock (train) plants and seeing some of the massive steel works one question that begs and answer is: if Kawasaki is making gas turbine power plants and jet engine then why do they bother with motorbikes and jet skies?

The answer is, of course, they make a lot of money doing it. In fact, they make more money selling consumer products than anything else. Apparently Boeing gets a better deal on jet engines than you get on your ZX-14.

According to KHI’s final report for FYE 3/31/2007:

| Kawasaki Heavy Industries | ||||

| Fiscal Year Ending March 31 2007 | ||||

| Total Sales | Profit / Loss | |||

| In Thousands | ||||

| Shipbuilding | $937,505 | 7.24% | -$19,037 | -3.26% |

| Rolling Stock and Construction Machinery | $1,564,764 | 12.09% | $111,525 | 19.11% |

| Aerospace | $2,293,124 | 17.72% | $113,473 | 19.44% |

| Gas Turbines | $1,674,308 | 12.94% | $83,301 | 14.27% |

| Plant and Infrastructure Engineering | $1,200,203 | 9.27% | -$20,586 | -3.53% |

| Consumer Products and Machinery | $3,496,367 | 27.02% | $233,407 | 39.99% |

| Other | $1,775,003 | 13.72% | $81,599 | 13.98% |

| Totals | $12,941,274 | $583,682 |

Out of the thirteen BILLION dollars in sales last year only 27% was from the consumer product division. However of their $583 million in profits, 40% was from their consumer division. That makes consumer products their most profitable division by a long shot.

Kawasaki remains very much tied to the Japanese domestic market with over 72% of sales being within Japan. Following the homeland the next biggest market is North America with 18%. That leaves a paltry 10% of revenue from the rest of the world.

Despite the history and breadth of it business enterprises and engineering prowess, Kawasaki, including the jets, the bikes, the ships, the marine engine, the power plants, the trains, is the smallest of the Japanese motorbike companies.

| Sales in Thousands: | FY 2006 |

| Ducati | $347,774 |

| Kawasaki | $1,130,331 |

| Yamaha | $1,352,176 |

| Suzuki | $2,347,396 |

| Honda | $8,468,373 |

Honda is, in fact, larger in sales than the rest of the companies put together. Just goes to show how good a rider Valentino really is and how unbelievable that those Bolognese are making the rest of them look silly in MotoGP.

I was invited, with twenty or so other American journalist, to tour three of Kawasaki’s oldest production facilities: Akashi works (motorbikes, robots, turbines), Hyogo Works (rolling stock (trains)), and the Kobe Works (ships, marine diesel engines, bow thrusters, top secret submarines).

Ordinarily such a visit would be a simple matter for your diligent correspondent. Shoot some pictures, whip off some snappy captions, fire the whole mess off to the editor and retire, stress free, to the nearest rotary sushi bar. Kawasaki introduced two wrinkles into my SOP. First, Kawasaki has hosted the press launch of their ZX-10 in Japan nary eighteen months ago. During that visit we were treated to a tour of the Akashi works assembly plant. I snapped photos, captioned it up and fire it off to the editor. The resulting work was published in the February 2006 issue of Roadracing World.

That sensitive photo essay was so comprehensive, so insightful and yet so entertaining that a copy of said article sits, matted, framed and behind glass in the museum at Akashi. It is, in fact, the only article hanged on the wall there. That soaring editorial achievement, however, doesn’t leave me with much to work with on a second trip to the Akashi plant a year later.

Secondly, KHI denied us our precious freedoms by denying the use of cameras in the works of Akashi, Hyogo and Kobe. This is a tragedy of unknowable proportions because the shipyard, in particular, was visually magnificent. Rising to the challenge to bring the truth to our readers, despite obstacles placed in our way is the Roadracing World way so I will endeavor to perceiver.

Our first stop was the Kawasaki museum on the Kobe waterfront. This museum is basically for children (as evidenced by the children, and Americans acting like children) but would prove useful at a later date for ersatz spy photos.

Akashi Works

See February 2006 Issue of Roadracing World or look on the wall at the Akashi Works Museum in Japan.

Kobe Works

Kawasaki has many production facilities centered in and around Kobe.

From the tourist park on the waterfront you can see the Kawasaki HQ

building (far left sky scraper) from which you can see the Kobe Works

ship yards. The tower in the center was built by Kawasaki as is the maritime

museum lurking under the whimsical spider works on the far right.

The Kobe Works has been located in the same location since 1886 but its infrastructure has been enhanced and updated. Over 1,100 ships have been constructed at Kobe including battleships, submarine as well as bulk carriers (ore, coal, etc), tankers, container ships, jet foils and liquefied natural gas ships. Currently there are about 2400 employees on the site working on ships as well as machinery and plant systems (chemical, energy or other types of factories). Most of a ship is assembled into modules which are then craned into place for final assembly. A massive bulk carrier takes about a year to build and will cost the final customer about $30 million. The shipyard can be constructing multiple ships simultaneously using a variety of module construction buildings as well as multiple dry and wet docks.

Ship bridge is installed on a bulk carrier in one.

Photo by Kawasaki

The history of shipbuilding is the history of cheap labor and raw materials. Labor is becoming increasingly expensive in Japan. That is, predictably, seeing the rise of ship building in China and Korea. Kobe Works, however, does not just produce ships. They also produce the specialized products used to power and control ships.

Starting with engines. Although you can get fancy (read: military) and power your boat with a gas turbine engine most commercial vessels are going to be using big two or four stroke marine engines. Now big, in this case, is measured by cylinders and stories.

Kawasaki builds both two and four stroke diesel engines for commercial vessels. For a basic bulk carrier (which is maybe 500 feet long) you might get a 5 cylinder engine that puts out 12,670 bhp at 89.4 rpm. The motor is about three stories tall and has doors in the crank case which are big enough for a small man to enter to service the big end bearings (which are a couple of feet across). Such an engine will be burning about 6000 pounds of fuel (750 gallons or so) but the ship has a fuel tank that can hold 2000 cubic meters of fuel (about 540,000 gallons) so the ship has a range of about 90,000 miles. If it is fully fueled and run everyday it won’t have to fill up again for over two years. Of course, it will cost about a million dollars to fuel it so if you lend out your bulk carrier make sure you tell your friend to bring it back full.

Since boys will be boys and the captain might take that motor to 90 rpm once in awhile there is a spare piston and connecting rod (the rod is about ten feet long and the piston is maybe two and a half feet across) hanging on the wall in the engine room. Installation can be done at sea using chain hoists and in place cranes. Given the attention to placement of the engine spares and the readily accessible installation cranes one almost gets the impression that is it not entirely uncommon to have to do a rod and piston swap.

Welding plate steel together in the shape of a ship is not exactly highly skilled labor but making diesel engines is. Kobe is shipping diesel engine to Korean and Chinese shipyards for installation in their ships. This, in and of itself, is a huge pain in the ass. Even the small engines weigh about 600 tons. The engines must be assembled (no small task) run, tested, then disassembled and shipped to the other ship yards.

When we toured the factory there were about four engines currently being assembled on the line all of the 10,000 to 20,000 bhp range. There was, however, a poster of a big engine on the wall.

This engine was the granddaddy marine diesel engine produced by Kobe. This one was twelve cylinders, stood six stories high and produced over 100,000 bhp. Ingloriously it was destined for duty schlepping container across the world. These pictures are not of this engine (see: ‘no camera rule’) but you can view something like what I am talking about here.

A modern big block diesel 2-stroke engine. Ten cylinders, six stories high.

Photo by Kawasaki

The cases are so big that they are not cast but welded up from plates. The bearings are enormous and the pistons are so big (with a cast combustion chamber) that they are virtually unrecognizable as a moving engine part.

In some ship applications it is easier to keep the engine spinning forward and, to reverse or change speed, change the pitch on the propeller. Kobe has all the required capacity to make controllable pitch propellers up to 33 feet (!) in diameter. They also make marine transmissions (no word if those jump out of gear as well) and giant bow thrusters. There is nothing like backing your container ship into harbor to look sharp in the pictures.

Giving a whole new definition to the word “Displacement”.

Archimedes would be proud. Photo by Kawasaki

Hyogo Works

Hyogo has long been the home of Kawasaki’s train division. It currently employs just under a thousand people who can produce eighty train cars and eight locomotives a month.

At Hyogo they build everything from the all aluminum 186 mph Shinkansens to mundane commuter subway cars. A stroll through the plant revealed about six different trains for six different markets being built simultaneously.

The size of the construction and the techniques used were not as impressive as the shipyard but the trains they produce are stunning. This first Shinkansen train was produced in 1964. Shinkansen actually means “New Trunk Line” and is not referring to the trains but to the tracks. The two are used interchangeably in day-to-day conversation.

Aluminum sheet construction of a Shinkansen locomotive.

To achieve the high speeds the train tracks have to be very level so there are many tunnels and bridges along the routes through Japan’s hilly countryside. Those tunnels create a few extra headaches because the train entering one side of the tunnel forces such a large mass of air out the other side of the tunnel that a resulting cannon effect of air occurs. These ‘tunnel booms’ have become an environmental issue and are preventing higher speeds from being developed. The tracks themselves are welded to minimize vibration and were of a standard wide gauge instead of the older narrow gauge used in Japan previously. Often the tracks are cambered (like a roller coaster) so the trains are actually leaning through turns. The passenger can barely sense this and instead it seems like the world passing by is just banking slightly from time to time.

Computer simulation study of the aerodynamics of the Shinkansens

in tunnels in an attempt to reduce tunnel boom.

The first tracks were started in the forties but not completed until the early sixties. Kawasaki delivered the first rolling stock for these new high speed lines with a top speed of 130mph in 1964. Some of these original trains are still used. The English term ‘bullet train’ probably has more to do with the aerodynamic shape of the first engines rather than the speeds that were being attained.

Shinkansens from the ages. The earliest type 0 ‘bullet trains’ are on the lower right.

These early high speed trains were so popular that additional tracks systems and trains have been added across the country. Not all train systems in Japan use the high speed train but they are by far the most popular way to travel if it coordinates with your needs.

The only downside of being an English speaker trying to utilize Japanese trains.

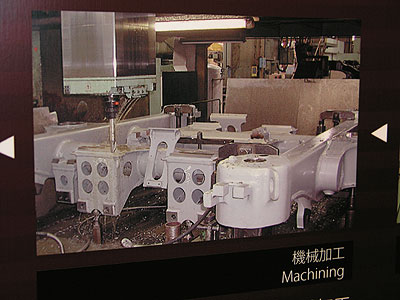

The Shinkansen trains have been through eight revisions from the original series 0 to the latest 800 series. The hand made aluminum bodies are truly works of metal art. The aluminum cars ride on trucks (the rolling bits with the wheels, motors and brakes) that, from a distance, appear to be large castings but are actually constructed out of many pieces of plate welded together reminiscent of the marine diesel crank cases. The trucks are then machined.

Machining of a train truck after the sheets have been welded to form the

chassis. One of the bizarre continuities between the different Kawasakis

factories was the period blaring of a simplistic midi version of the song

"Itzy-bitzy Spider” over the PA system. No explanation was offered.

The metal work is impressive but is not nearly as involved as the interiors of the cars. The wiring harnesses for carrying electricity, data, sensors and controls for each seat are massive and complex.

The Shinkansen trains are so comfortable, quiet and elegant that it is tough not to immediately order one for your own private utopian society. Unfortunately the Hyogo works are sold out for the next two and a half years.

Fast train.