Michelin Revolutionizes Performance Street Tires with the Power Pure

Almeria, Spain

March 9, 2010

Sam Q Fleming

Although I lag behind the US Supreme Court in anthropomorphizing corporations, I get the distinct impression that Michelin is pissed. The $20 billion tire company has repeatedly revolutionized motorcycle tires (radials, dual compounds, penta compounds, infinite compounds, race tires built on demand) only to find themselves locked out of the top levels of competition the world round: MotoGP (spec Bridgestone), World Superbike (spec Pirelli) and the once illustrious AMA Superbike (spec Dunlop).

Michelin dominated both MotoGP and Superbike when allowed to use the full brunt of their rapid tire manufacturing and compound development expertise. They manufactured race slicks that had a soft layer on the outside for a couple of laps, a more durable compound in the middle of the tread, then another soft layer at the end of the race when most tires were fading because the worn rubber could no longer generate enough internal heat. As a result Michelin tires ruled the world championship podiums.

Fast forward three years and Michelins cannot be found on any of the top grids.

Seething at the loss of competitive outlets, Michelin conceived a two-part strategy that has finished its gestation in 2010. First, they have devoted themselves to the Spanish, Italian and World Endurance championships and have posted $3,000,000 in contingency money in non-DMG American racing. Second, they have set out to erode the financial bases of Pirelli, Bridgestone and Dunlop by, namely, bringing the full weight of their $750 million annual R & D budget to bear on the only competition that really matters: the battle for the wallets of customers.

With the birth of the Power Pure model line, Michelin has revolutionized motorcycle performance street tires. While this tire is not for racing (except maybe in some cold and semi-wet conditions when nothing else is going to work), Michelin has created a hypersports street tire that is actually a true lever on performance enhancement without sacrificing tire life.

There are two basic types of weight on a motorbike: sprung and unsprung weight. Sprung weight is everything (including the rider) that rests on top of the springs. Most of the weight of a motorbike is sprung weight. Sprung weight is relatively simple to eliminate with wrenches and money: smaller battery, titanium pipe, unbolting non-required equipment, thinner bodywork and so on. However, as you reduce the sprung weight for better handling and faster acceleration, you have introduced a complicating dynamic. The ratio of unsprung (wheel, tire, axle, brake rotors, brake calipers, fork lowers, fork oil) to sprung weight has worsened. Every bump is now going to hit a little harder because the heavier unsprung weight is going to have more of an effect on the now lighter chassis.

The Power Pure are OEM tires on the 2010 R1, giving Yamaha the easiest 1kg weight reduction ever. Really this caption should be with a picture of Sam riding an R1 but the only R1 at the launch was a French market model that is restricted to 106bhp. The cops in France actually have dynos by the side of the road and if your bike makes higher than 106hp they take your bike and pull your license. It is ignorant to malign France for military prowess (remember Napoleon?) but it is fair game to mock them for passing a law mandating slow bikes.

Rotating unsprung weight (tire, wheel, rotors) creates large gyroscopic precession forces. These gyroscopes follow their own rules. A spinning wheel that is twisted will attempt to twist back with an equal force at 90 degrees. Simply put, the lighter the front gyro, the easier to turn and the more stable the motorcycle. Some of that increased stability can then be sacrificed for even more aggressive chassis geometry allowing for an even more nimble ride.

The problem is that reducing rotating unsprung weight has drawbacks. Smaller or thinner rotors don't work as well as larger or thicker rotors (we'll skip carbon rotors for the moment), magnesium wheels are more fragile (and much more expensive) than aluminum, forged rims are more expensive than cast rims, and you really need to have a tire on the rim. But the advantages are undeniable which, in some years past, saw our team only buying lighter front rims to pick up the handling advantage, but on a budget.

Lastly, the inertia forces of the wheel are calculated as “mass x radius squared”. In other words, weight far from the axle has an exponentially greater effect than weight close to the axle or, simply put, the tire weight matters a lot more than the rotor weight.

So Michelin decided to build lighter tires. Really light tires. 1 kg (2.2 pounds) lighter. That is the same as dropping 6.6 pounds off the rims or 8.8 pounds off the rotors. Those are crazy numbers. These tires are dramatically lighter than their competition: the Bridgestone BT-016, Dunlop Qualifier 2, Metzeler Sportec M3, and Pirelli Diablo Rosso.

Basically, mounting these tires is akin to unbolting 1.5kg from

Basically, mounting these tires is akin to unbolting 1.5kg from

your spokes as is demonstrated by a Michelin technician.

Now, making a light tire as a gimmick would be pretty easy; making a light tire that gives up nothing in grip, longevity and price is a tour de force in French engineering.

To reduce weight you need to either use less material or use a lighter material. The second one was pretty easy. Michelin replaced their metal fiber carcass strand with a synthetic Aramid fiber which maintained tensile strength but at 10% of the weight.

The first is much more devious. Popular conception is that friction between the tire and tarmac is what warms the tire. That is not the case. While that friction warms the surface of the tire, the real heat is generated by the internal friction in the tire’s carcass rubber created by the tire flexing. This is why lower tire pressures (more flex) typically lead to higher tire temperatures. It is also one of the reasons why race tires tend to fade as they get thinner. The less rubber, the less internal friction and, therefore, the less heat. That is why Michelin puts a softer compound towards the bottom of the tread depth of their highest end race tires, which makes them work even as the tire temperatures fall thus allowing Rossi to put in his fastest laps at the end of the races.

The tread pattern and rubber compound are both derived from Michelin’s racing rain tires, ensuring that the Power Pure performs on dry, wet, cold or hot.

The tread pattern and rubber compound are both derived from Michelin’s racing rain tires, ensuring that the Power Pure performs on dry, wet, cold or hot.

To reduce the weight of the Power Pure Michelin needed to use less rubber but without reducing the tread depth; they had to reduce the amount of that sub-tread heat-generating rubber. Reducing that rubber meant the tires were going to run cooler, so Michelin reached in its bag of compound tricks and pulled out the Silica rubber. In short, carbon black tires will ultimately give the most traction on a dry surface but they are highly temperature dependent (hence the proliferation of the now ubiquitous tire warmers and generators). The downside is that carbon black tires are severely impaired on a wet surface as well as when asked to operate outside of their designed temperature comfort zone. Silica compounds work very well on dry or wet surfaces (something about molecular spacing allowing the water to actually soak into the rubber) as well as working at a very wide temperature range. Basically, they work cold.

Since the compound works at lower temperatures Michelin could eliminate much of the base layer of rubber and its subsequent weight without sacrificing longevity since the tread depth remains constant.

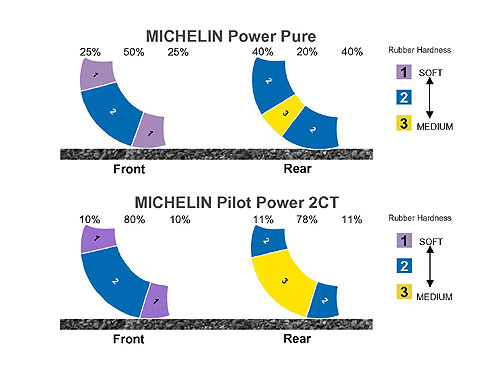

Michelin then used its construction tricks in making both the front and rear dual compound tires. The original 2CT street tires (2005) were heavily influenced by Michelin's race tires. To that end the softer rubber was only available at extreme lean angles, lean angles that are basically never achieved on the street. The softer edge rubber was just for apexes, not for acceleration.

The older CT2 tires required the harder compound rubber to extend to the acceleration area of the tire to prevent premature wear. The new Power Pure is optimized for street riding such that the softer compound is more immediately accessible to the rider. Changes to the compound chemistry enhance both grip and durability.

The new dual compound profile in the Power Pure puts the rider on the softer compound almost immediately off center. The rear tire has a band of harder rubber in the middle with softer grippy compound available at the first hint of a lean angle. The front matches this basic design but with even softer compound rubber available for braking or turning.

End result, the Power Pure is a track day / street tire that is dramatically lighter than its competition, that works well in dry, damp or wet (puddled) conditions and that won't rapidly center crown as you ride the freeway to get to the mountains. It also works in temperatures from 35 degrees to 100 degrees so you don't need to keep your commuter bike on tire warmers to be able to make it around the first entrance ramp.

Solid grip, wet or dry.

Solid grip, wet or dry.

Press launches are, by necessity, artificial riding experiences. The time is brief, the bikes are unknown quantities and the weather is unpredictable. The Power Pure launch was a combined street and track riding event held in the beautiful southern Spain region surrounding the Almeria Racetrack. Southern Spain is known for its temperate Mediterranean climate but the day of my arrival saw a plummet in temperature and a grey skied steady drizzle.

My first track session (out of two!) was going to be on a cold, puddle strewn, soaking wet track. Michelin had arranged for an array of motorcycles so I grabbed a Ducati 1098 figuring its torquey motor would be forgiving in the treacherous conditions. However, the moment I sat down on the seat I knew I was in trouble. The forks were totally lacking in damping of any sort and the springs were soft. The adjusters were tiny allen heads so I couldn’t resort to my five second press launch trick of using the ignition key to surreptitiously adjust the rebound damping setting. Combined with the powerful Brembo brakes and no track knowledge the bike lurched, wobbled and wallowed its way around the track. I had absolutely no feel for the front tire at all. The rear seemed planted and didn’t slip or spin but the wet noodle forks obfuscated the front tire.

“The sun was warm. The tarmac dried. The Bimota’s engine moaned.

The rider was disillusioned. He rode on. The tires gripped. The photographer shot.

It was enough.” For Whom The Road Curves – Ernest Hemingway

For the second session I simply walked around to each bike and bounced on each front end to find the best one. Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. Much to my surprise the best forks were on a ZX10. The track was ideal for tire testing, and nerve wracking for riding. There was somewhat of a dry line that had formed but some sections of the track were still wet, some otherwise dry corners had water streams across them, and puddles seemed to remain, on line, just after the blind crest of every apex.

With the damped forks I could start to investigate the Power Pure’s front tire wet grip. Although I knew the compound bears some similarity to the Michelin racing rain tire I was still surprised by the tire’s absolute indifference to the presence or absence of water. I would arc through a turn on dry pavement and, as my line crossed a puddle, I would expect the brief tuck of the front tire losing grip, but it never did. Eventually I was dragging my knee across puddles…on a street tire.

Press launch street rides in Spain are an exercise in suspending a belief in consequence. Spanish mountain roads are frost heaved and rutted, and have diesel spills, no run off, blind access, trucks, mud, puddles, damp shady spots and, perhaps most dangerous of all, roadside photographers.

That would be a Bimota Tesi 3D. It's got an aircooled two valve Bolognese desmo with a

wacky center hub steered chassis resulting in a heady combination of low power, nervous

high-speed manners, poor suspension and an indifferent front feel. In hindsight it was not

the most practical of choices for a 100 mile high speed (130 mph plus) blast around

Spanish back roads but such is the allure of an exotic Italian.

For some reasons beyond my immediate comprehension, of all the bikes available for my selection I chose to ride the Bimota Tesi 3D. The Bimota is fitted with an air-cooled Ducati 1100 engine but it felt dreadfully underpowered when trying to maintain over 200 kph (120 mph) on the Spanish back roads. It was the first time I had ridden a hub center steered bike and, truth be told, it probably wasn’t the best choice for tire testing but sometime the uniqueness of an experience outweighs practicality.

Although the bike and I didn’t always see eye to eye on every issue (speed, handling rough roads, wooden brakes, quirky suspension behavior) we did part as friends. Throughout our time together (where I flogged that Italian exotic mercilessly) I never felt as if I was approaching the limits of the tires.

The devil's advocate would point out that 90% of street going bikes would get the most economical handling benefits with a tire pressure gauge (seriously, street bike rarely have the correct tire pressures), correctly adjusted (or replaced) steering head bearings, and suspension settings that closely resemble proper settings. However, the 10% of street riders that actually take their street riding seriously enough to set sag and check tire pressures will relish the transformative effect these tires will have on a strenuously ridden street bike.

Remember about geometry! If you actually set the geometry of your bike for the tires that

are currently mounted, remember to measure the diameters when you switch brands as

most Pirellis and Dunlop tires are smaller than Michelin tires. You may want to raise the

back 7mm to 10mm after mounting the Michelins. However, if you never did anything to

your geometry to begin with, forget you read that previous paragraph. Your correspondent

has absolutely no idea how one even adjusts rake and trail on a Tesi 3D.