Autopolis, Japan

All Japan Road Race Series

Kawasaki Media Tour

May 28, 2007

Words and Picture by Sam Quarelli Fleming

As part of the good will junket of Japan by Kawasaki the collective American journalist contingency was treated to two days at Kawasaki’s magnificent race track: Autopolis. The first day was a during the fourth of the seven round Japanese national race series. The second was a track day for interested journalists.

Diligent readers of this paper were introduced to Autopolis in your correspondent’s review of the ZX-10 in December 2005. The geographic grandeur, utopian architecture and evocative macadam make Autopolis one of my three favorite race tracks in the world (the other two being Mugello in Italy’s Tuscany and Phillip Island in Australia’s Phillip Island). Autopolis is the legacy of hubris and exuberance of the Japanese economic bubble of the early 1990s. The construction of Autopolis is rumoured to have cost upwards of $300 million but the track and four star hotel on its premise never opened as the construction was completed just as the world’s investor did a collective “WTF?” at the valuations of Japanese stocks and real estate (at the time a single sky scraper in Tokyo was valued more than the entire stock exchange in Australia).

The tumbling asset prices (both securitized and un-securitized) created economic hardships from which the Japanese economy has yet to recover. Assuming 7% loans with a twenty year term the original owners would have been looking at payments of about $2,335,896…per month. That’s, roughly,$77,530 per day. Unable to find the 1,000 track day riders PER DAY that they would need to meet those notes the track went into default.

The track was largely abandoned for the next fifteen years. Kawasaki ended up buying it for a song (rumors say $10,000,000, they’d only need about 30 track day enthusiasts per day to pay that note) tore down the vacant hotel, painted the corner stations and started using it for testing and races.

My previous visit had been to a ghostly empty venue that seemed more like a study in neutron bomb after effects rather than the heady humanistic cocktail of adrenalin, fear and exhilaration that courses through the pits of an active track. Eighteen months later I am back on the rim of an extinct volcano surveying the vibrant pits filled with racers, families and enthusiast. Steeling myself against an insurmountable language barrier and armed with a VIP pass and my camera (finally) I delved into event.

Autopolis, (translate into greek?) before the hotel was razed

in November 2005.

Autopolis sans hotel with a portion of the day’s 20,000 spectators. As real

income has dropped in Japan the attendance by both racers and fans has

been slowly dropping at the motorbike races.

The AJRR series is the only national roadrace series in Japan. The classes

are all actively contested and are as such: Superbike 1000s, ST-600s,

GP 250, GP 125 and GP Mono. The 1000s are allowed reasonably

comprehensive modifications including cams, transmission, headwork,

exhausts, suspension, frame bracing, replacing the brakes, swingarm,

wheels, suspension and ECU. The 600s are basically superstock machines

with optional ECUs, suspension and exhausts. Bigger teams get to use the

garages, smaller teams are in the next lane back. Many teams were racing

out of crowded van without so much as a three-rail trailers. The transporters

are small but the riders are fast.

Daigo Fukuoka (the last name is also the name of a city in Japan) in his

Elf hat poses with a competitor and his 250cc 4-stroke GP bike. I am sure

if I spoke Japanese I could have heard him espouse on the virtues of racing

pure bred GP machinery which are easy to work on and how the GP riders

all stick together in the pits. These bikes use custom frames housing modified

versions of the 250cc four stroke single engines the big four produce for

dirtbikes. As a GP class the modifications seem to be pretty unrestricted

beyond four stroke single and displacement. These bikes are available

in a ready to race format from a variety of suppliers for about $10,000.

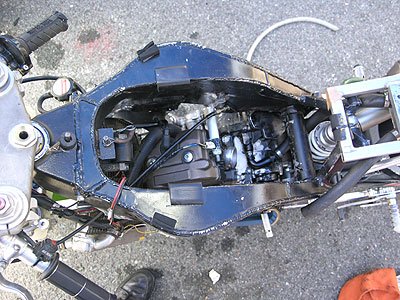

Top view of Fukuoka’s Kawasaki GP-mono bike with the carburetor removed

for a re-jet. Dirt bike technology means old fashioned coil ignition (boo-hiss)

but with huge sparred frame and lightweight. This one is powered by a

KX-250F motor fitted to a MARS original frame. I believe the whole package

is available from Miyawaki. It puts out about 39ps and has a top speed of

around 180 kph.or about 115 mph. These look like they would be very

fun to ride.

I am not sure if even a heavy breathing single needs a breather box quite

as large as this one but perhaps without an airbox it’s a good idea.

With a weight of only about 80 kg (176 lbs) a single four piston Brembo

is fitted to the front of most GP-Mono bikes.

The GP-Mono bikes are fitted with massive flat slide carbs.

The typical racer cookout in Japan features (from the back) a ricer maker,

a tea maker and an electric skillet.

I have no idea what the deal is with these little dolls but many of the

big teams were giving away little umbrella girl figurines in the pits.

This is pretty existentialist if you stop to think about it. Even winning

multiple championships and winning the love of his high school sweetheart

will not end his challenge. There will be no contentment in this young

man’s life until the grave. I salute you number 56.

This group, as far as I could tell, are in their early thirties and all rode their

motorcycles to the track for the races. At least one of the women was riding

her own streetbike. One of them is a journalist, another is a mechanic for

automatic sushi machines, another works for the municipal government

and another works in a record store. They were mainly riding naked 1000s.

The entire exchange of information was conducted mainly through sign

language and smiling so really whatever you make up could be just as

accurate as what I wrote down.

Trick Star is a top ten 600 team. They ran two bikes in the race.

This is their truck.

One of Trick Star’s 600s on the grid for the 600 race. In a tribute to

efficiency Japanese racers can purchase “White Body Machines”. This

allows them to buy a bike straight from the factory floor without any

of the street equipment which would be summarily tossed during the

race preparation. The “White Body” bikes come with no lights, no

registration and no exhaust pipe. Kawasaki sells about ten to fifteen

ZX-10s and about thirty ZX-6s each year in this state. This saves racers

a bit of money on the up front costs as well as bypassing the regulations

governing the sale of powerful motorcycles in Japan.

The women of Trick Star. Two are full-time, two are temps.

Tools are universal.

Every garage in Autopolis has a TV with the current running order and

scoring information. The top six positions are fixed while the rest of the

display scrolls through the results. On lap 13 of 16 a Yamaha runs in first

(there is no way to know that from this display) while the top Kawasaki

runs in 6th. Naoko (number 99) runs in 24.

A Trick Star mechanic relays timing and scoring to his rider.

Post race debrief.

After each race the pits were opened up spectator to talk through

and take pictures of the riders, the bikes and the models.

This is the generator for one of the big teams. I’ve seen guys show up

to track days in the US with more gear than some of these top Japanese

Superbike teams had. That said, Japan is a nation of about 150 million

people (roughly half the size of the US for those of you who have not

been paying attention) so the fastest racers in Japan are very fast.

Racer’s van for a top rider.

This is Naoko Takasugi. She is thirty years old and, although she has been

racing for ten years, she has only been riding 600s for four. Her 600cc

bike will remain a mystery because its manufacture did not drop $10,000

for my trip. She, however, is a total bad ass. She weighs 88lbs and stands

about five feet tall. She qualified in the middle of the grid out of 40 entries

and was turning consistent 2:00 lap times. For comparison the fastest lap

in the race was a 1:57, the fastest any of the US racer/journalists went the

next day (granted on stock bikes with only so-so tires) was in the 2:06 range.

Japan’s state religion was Shinto until 1945. This is a combination of

state/emperor worship combined with the appreciation of gods’ work in

natural beauty or process. The Emperor of Japan is a direct descendant of

the religious leader who settled Japan with his followers from the mainland

and, until a formal renouncement of status in 1946, the emperor claimed

to be a living god. This ancient religious practice influences Japanese

traditions of culture, art, architecture and community. Besides selfless

obedience to the state/emperor a central tenet of Shinto is the reverence

and love for natural artifacts. At Autopolis this philosophy manifests in

appreciation of some fine Japanese ass in black vinyl high heels.

Nassert-Beet is a Japanese manufacturer of what appears to be some very

tasty exhaust pipes and rear-sets. Although they mainly focuses their racing

efforts on the eight-hours of Suzuka they are running a few of the superbike

rounds on their ZX-10.

The Beet bike with a race KYB shock, some sort of trick linkage, folding

shift lever (endurance legacy), quick shifter, engine breather box (in

front of shock) but a conspicuously stock swingarm and pivot placement.

Beet racing gridded for the superbike race.

32 year-old Koji Nazaki expresses self-incrimination over the scuffed fairing

of his ZX-10 superbike. Koji works as a test rider for Kawasaki based out

of the testing department located in Building 38 of the Akashi works.

His co-workers help with the team hence the name “Team 38”. His bike

puts out 186ps, tops out at about 290 kph and weight 187 kgs (dig

the magnesium rims). His best finish to date is a 16th.

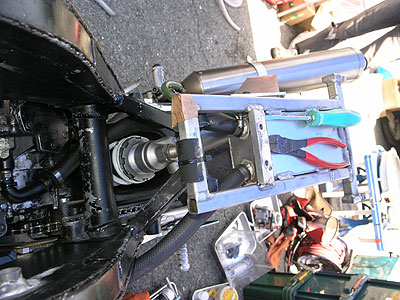

I don’t know who built it or what handling problem it was installed to

cure (grip? bump steer?) but this is a back of the grid superbike with

a custom swingarm.

You have to really want to lower your swingarm pivot to hand build

offsets and run an undersized pivot axle.

Akira Yanagawa qualified 2nd and finished 2nd after

leading the race for about half distance and a long dual

with two Suzukis.

Typically endurance racers are the most mechanically paranoid and

pessimistic. Apparently Akira’s mechanic used to endurance race since

he brought a spare shock and ECU out to the pre-grid.

Akira’s view of the start of the superbike race.

The Japanese take food very seriously. Being at the racetrack is no

excuse to slum in the cooking and eating departments.

Akira leads on lap three.

Valentino fan.

Running in fourth this rider made a desperate two position pass up the

inside into turn one. From 200 yards away it was clear he was not going

to make it stick. He tagged the rear wheel of one of the leading bikes

and cart wheeled into the gravel trap.

Even the bike goes in the van to the track. The fold down rear seat /

bed should be immediately adopted by Ford.

On the Monday following the races our press flack handlers had arranged

for a track day at Autopolis. Apparently this lead to some complicated

cultural negotiations since a ‘track day’ in Japan means hanging out at

the track with your friends drinking beer and smoking cigarettes. A track

day in the US means riding pretty motorcycles around in circles.

Fortunately everyone was able to get the semantics worked out and

we had two ZX-6s, a detuned ZX-10 and a ZX-14 between a dozen

or so of us for the day.

All alone at Autopolis; I don’t even want to know what this lap is costing.

A turret house at Kumamoto castle. It is a stretch to

include a picture of Kumamoto castle in this story

because it 90 minutes from the track and has nothing

to do with Kawasaki or racing but since it is unlikely

that I will ever have the opportunity to use this picture

at a later date, here it is. Consider it a Shinto appreciation

of natural beauty and state power.