Roehr 1250cc

September 5, 2008

By Samuel Quarelli Fleming

Photos by Tom Riles

Walter Roehrich is very nervous. It’s 10:30 a.m. on an overcast day in northern Illinois and he only slept a couple hours last night before arising early, making sure he had the press materials and the coolers with drinks and even remembering to stop at the Dunkin Donuts for hospitality supplies for the day. He has invited four journalists to Blackhawk Farms race track to pass judgment on the Roehr 1250sc, the physical culmination of fifteen years of work, and he wants everything to be perfect. The fact that the remnants of Hurricane Gustav had just barely cleared the area is not helping his nerves.

Roehrich is the lead designer, head engineer, marketing director, production manager, procurement specialist, business partnership negotiator and contract manager for Roehr Motorcycles LLC. In fact Walter is the sole employee of the company.

Walter Roehrich, 46, grew up primarily in Illinois. His formal training with machinery began with the Spartan School of Aeronautics with training to be an aircraft mechanic. He soon moved from airplanes to working on Porsches and Audis and relocated to Long Island, NY to work as a professional mechanic.

He moved back to Illinois in 1992 to work in various management capacities at automobile dealers until a couple of years ago.

Although he raced dirt bikes he has never been a motorcycle road racer. He has always had a strong affinity for Italian designed motorcycles and that love is expressed in the lines and components of his creations and even his current business model.

Though he was working day jobs to support himself and his family he has been designing and building motorcycles for years. His first project commenced in 1992 when he started on the RV500. The RV500 was a 500cc two-stroke twin using Yamaha motocross 250cc top ends and cranks. He had his own cases cast by a firm in Bensenville, Illinois and then did the finish machining himself. He made a frame to house the engine, constructed his own swing arm, made his own gas tank, and used TZ 250 bodywork. Although the project generated substantial enthusiasm amongst two-stroke fans it did not end up not being a viable business project.

Undaunted by the work, from 1996 to 2000 he built the RV 1000 with a Swedish V-twin motor that was a derivative of a Husqvarna single. It was a lightweight and, for its day, powerful engine platform. Unfortunately the engine importer dried up and so did the commercial prospects of that project.

In 2002 Harley-Davidson released its Porsche-engineered V Rod engine and Roehrich immediately began the design for a sport bike based around that motor. Although he completed the initial design in about four months, he had to wait a couple of years for the price of used V Rods to come down while he negotiated with his very understanding wife for the inclusion of the donor bike into the family budget.

Since America has given up much of its manufacturing base, he shopped extensively in Europe for components. He finished his first Harley-Davidson-based prototype in 2006 using the 1130cc version of Harley’s liquid cooled engine.

What seemed like a potent, albeit heavy, engine in 2002 for the cruiser market was hopelessly outgunned in the sportbike sector in 2006. With 600cc bikes dynoing triple-digit horsepower, the anemic output of Harley’s now 1250cc Revolution engine was still going to be laughable to sportbike riders.

Roehrich did not want to build an apologist American sportbike so, following in the footsteps of his airplane mechanic forefathers when facing superior foreign horsepower, he fitted a supercharger to the 1250 Harley engine.

Whatever your brain thinks of the engineering, the engine has irresistible appeal to the heart.

At its simplest a gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine is an air pump. The more air the engine can pump the more power the engine can make. Hence, the simplest way to boost power is to pump more air by either making the engine displacement larger (ie, go from 600cc to 1,000cc) or pump the air faster (spin the motor at 17,500rpm instead of at 12,000).

If you are constrained on displacement (racing rules, market segments, insurance, etc.) and you are constrained on RPM (price point, mechanical failures) then you have to start looking at efficiency by reducing parasitic losses and optimizing the thermodynamics of the combustion process. That leads to more compact combustion chambers, waisted valves, low friction coatings, better crankcase breathing, straighter ports, better fuel injectors, more precise engine control units, fewer engine bearings and all the myriad tiny refinements which have allowed 600cc engines to enjoy horsepower gains of 50% in the last ten years.

Don’t price it compared to sport bikes, think of it

as a signed print by a yet to be famous artist.

As Roehrich was using someone else’s engines (and is being treated like any other custom builder by the H-D factory) he could not control the development and engineering that would be required to refine the internals of the Revolution engine. He could, however, overcome all of the engine’s thermodynamic and parasitic loss limitations by adding the supercharger.

When the combustion chamber thermodynamics are sub par,

boost the manifold pressure and bring the noise.

Whereas a turbo charger captures waste heat from the exhaust system and uses it to drive a compressor for the intake tract, a supercharger skips straight to the point and mechanically drives a giant fan to blow air into the intake tract. Forget ram air, this is forced air with a capital F.

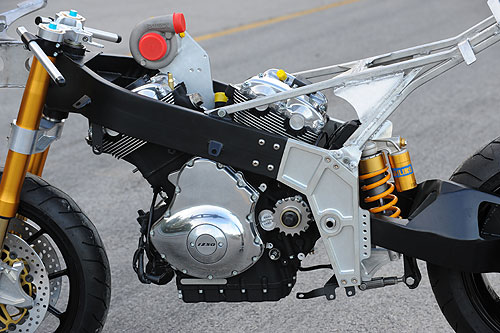

The Rotrex supercharger is from Denmark. It is a centrifugal compressor with a planetary roller drive. The supercharger is driven off the intermediate cam drive shaft by a toothed carbon fiber poly chain belt. Whereas the best ram air systems might be able to keep the air box pressure from dropping too far into vacuum, the Rotrex is set up to max out the plenum (the intact tract on forced induction engines) with 8 lbs of boost to the manifold. That is huge. That is like adding an entire half an atmosphere of pressure for the engine. It is, roughly, like increasing the engine displacement by 50%.

The addition of the supercharger required replacing the stock injectors with Destroyer injectors that can flow 50% more fuel. In addition the Roehr 1250sc picks up a little efficiency from the new injectors as they have six holes whereas the stock Harley injectors are only four hole units. Roehrich was able to map the fuel injection on the supercharged engine using the stock ECU with a Harley Race Supertuner.

There wasn’t much Roehrich could do about the ponderous mass and weight of the Harley powerplant but at least the engine output was now in the modern era.

After eyeing the lack of run off at Blackhawk Farms raceway I walked around the Roehr warily eyeing the assembly and components on the only Roehr 1250sc in existence and trying to organize my thoughts about the bike.

Roehrich’s justified love of the Italians is obvious. The bodywork (built by top quality American manufacturer SharkSkinz) is reminiscent of the Taglioni Ducatis and MV Agustas. The Brembo brakes and Marchesini wheels would be familiar on any high end Italian sport bike. The Ohlins forks and shock immediately say more about the intended price point for the bike. The discredited side mounted radiators are reminiscent of the short-lived RC 51.

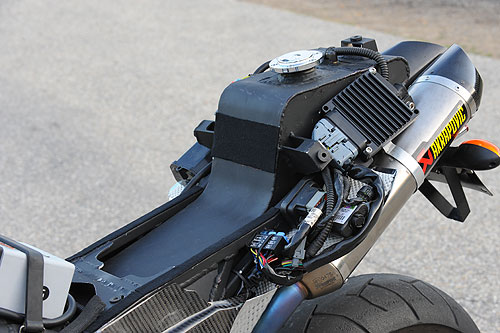

The custom exhaust system is created with a header manufactured by Vance & Hines mated to Akrapovic mufflers which would look familiar on an R1.

Unique chromoly sheet single sided swingarm. The machined aluminum swingarm plates

are press fit, then bonded, then bolted to the chrome-moly sheet frame spars. Carbon trim

panels cover up the aluminum subframe while a pricey Ohlins shock adds a dash of color.

The whole effect is slightly diminished by the GSX-R rear sets.

Sculpted gas tank puts the fuel weight a little higher and farther back than

ideal but is offset to some degree by the light Akrapovic mufflers.

The frame and swingarm are particularly interesting pieces. The frame is constructed of folded and welded chromoly sheet to create the headstock and spars. The spars are then epoxied and bolted to machined aluminum swingarm plates. The frame does not use the engine as a stressed member; actually, the engine is totally rubber mounted which reduces vibration to the rider to a bare minimum. The single sided swingarm is also constructed using laser cut chrome-moly pieces that have been painstakingly welded. The subframe is hand built out of aluminum and shrouded by the carbon fiber trim pieces. The diminutive 3.2 gallon gas tank lives under the seat and extends up above the mufflers in the tail section. The frame, swingarm, subframe, gas tank and fairing stay are all domestically produced by the American frame maker FrameCrafters (well known in vintage racing circles) and the whole effect is cheapened a bit by the appearance of stock GSX-R rear sets.

Removing the sleek bodywork reveals purposeful components

reminiscent of a World War II fighter plane.

So now it comes down to a drying racetrack in the backwoods of Illinois and one of the world’s most jaded motorcycle journalists thumbing to life the sum total of another man’s dreams while his wife, brother and uncle look on.

The bike has a nice ergonomic position. The bike does not feel big or ungainly. The narrow spacing on the clip-ons is reminiscent of the R-6 or a Ducati but the comfortable seat and knee friendly rear-sets allow for a comfortable yet racy posture. The sc would be an “all day” sportbike. The throttle is a very aggressive 1/6th turn or so giving a heavy throttle pull which results in a disconcerting contrast to the incredibly light hydraulic clutch.

It would be much more comfortable for an all day ride than most modern sportbikes.

Of course, at its price point you could also pick up an F150 in which to carry your

uncomfortable sportbike to the curvy part of the trip.

The transmission goes into gear with a light and positive touch but halfway through the fourth turn my heart sinks. The handling is all wrong on the bike. It weaves, it wallows, it crushes its forks with the weight of the engine and overwhelms the traction of the front tire. This creates a trepidatious and tentative riding experience. With cornering out of the question I tried to focus on the other characteristics of the bike. The transmission shifts surprisingly well, the brakes (despite using an old style Brembo master cylinder) are sufficient to convert the bike’s ample potential energy into heat and the heavy throttle is at least wrist friendly as it doesn’t take a lot of effort to get the thing to WFO.

Roehrich was probably a week of track development early for having the journalist come

to judge the capacity of the bike. Based on our feedback Roehrich promised further

suspension revisions before production.

Despite the dyno chart documenting the rear wheel 167 bhp at 9,200rpm the engine feels surprisingly docile. The heavy flywheel takes a lot of the snap out of the engine and the linear power delivery with 320° of tire traction recovery time between engine pulses belies the power of the supercharger. The bike pulls smooth and clean from any RPM and eats the 2500 rpms between third, fourth and fifth in just a few seconds. However, the low (and harsh) rev-limiter and the five speed gearbox impose on the fun. Taller gearing might work better for this bike to allow more room between the gears.

Blackhawk is a tight course which meant that just as soon as I could begin to appreciate the exhaust note (and the bike does sound great) I would have to wobble and squirm my way through another turn in fear of tossing the bike into the weeds and, worse, scratching my pretty helmet.

An exhaust note like a P51 in a power dive.

After four laps I returned to the pits with the philosophic air of human endeavors replaced by a cranky racer. I have built enough race bikes to know the desire to have Spies, Hayes, etc. declare your motorcycle the best handling thing they had ever ridden.

“What do you think?” Roehrich asked, with a bit of trepidation generated by my silence as I removed my helmet and stared at the bike.

With the tact and diplomacy that characterize my motorsports career I responded “Why are we here? I mean, am I here to review the bike that you have handed me to test and compare it to other production sport bikes or do you want me to try to develop it as far as we can given the limitation on parts and the time at hand?” This is the sort of tragic outburst that comes from delayed flights into O’Hare and late night drives to god forsaken race tracks.

“Let’s try to set it up” said Roehrich gamely.

Roehrich has made a couple of mistakes with the setup of the bike. The first mistake, all too common, is people buy expensive components but do not know how to configure them. The Ohlins forks were not sprung or valved for this motorcycle. The spring rates (unknown at the track) were too light for the forward weight bias of the bike. Since the springs were a little light the bike was riding too far down in its stroke. Because a bike’s steering geometry is dynamic, the rake and trail numbers are theoretical. The actual rake and trail of the bike will differ at any given time depending on brake load, side load, traction, and bumps. The bike was built with steering geometry that is overly aggressive already: 23 degrees of rake and 89mm of trail. With the soft fork springs the Roehr was running something closer to 21 degrees and 79mm. This removes any feel from the front tire and causes the bike to be unstable at lean while still being on the verge of crashing. Even with proper fork springs that steering geometry might be too aggressive for this chassis. It would be easy to condemn Roerhich for this error but given that Honda, which is about a billion time larger, did exactly the same thing with their 929 it makes it all a little more understandable. With no alternate springs we did the best we could with the damping settings.

The side mounted radiators allow for more room between the front tire and the front cylinder but are probably a little overwhelmed by the 170bhp. Even at cool ambient temperatures the fans (switched to run over 200 degrees) were constantly spinning.

Secondly, Roerhich had used a couple of Buell racers to do his baseline set-up. Most racers do not actually know how to set up a bike. They just know how to take a bike to its current limit. The Buell guys should have felt the same things we were feeling but they either were not riding hard enough or are working in an alley where they can’t see out. Overly aggressive chassis geometry feels great when you are going slow but it is unforgiving and nervous at even a moderate track day pace. A suggestion to anyone working on building a new bike: bring a box stock GSX-R 750 straight from the showroom floor and use that as your control instance to which everything should be compared.

Thirdly, the head bearings were too tight. Most racers only bring rear stands and, if they have a front stand, it does not allow free movement of the forks. This makes checking head bearing tension cumbersome and thus huge numbers of bikes take to the track every day with notched, over tightened or loose head bearings. We were able to adjust the head bearings on this bike by pulling it up on the sidestand and wiggling the wheel until we got free movement in the steering. We also reduced the tire pressure from the street settings of 34/30 to 30/30.

With these revisions the bike was much better but still had peculiar handling. I tend to believe that the lack of front end feel is the overly aggressive geometry exacerbated by the under sprung front but it could be that we were getting into frame flex. Only more time on the bike and more parts selection would tell. The spars on the frame are steel (stronger than aluminum) but are not tied into the motor (like on virtually every other sport bike) so the frame may be more comfortable on long rides (which is what the bike is intended for) but may not give razor sharp handling (which is what you look for on the track, like, say, where I was riding it). Of course the rubber-mounted engine meant that there was little to no vibration in the bars allowing my hands to go numb from my chronic carpal tunnel instead of engine vibration.

As tested the gearing was maybe a little short. With its the ample torque the bike goes straight to 12:00 on the throttle in first gear making wheelies a little uncontrollable. With the way the bike eats the rpm between the gears, adding a tooth to the front would probably camouflage some of the shortcomings of the five speed gear box and allow more room through corner combinations instead of running out of rpm halfway around a long increasing radius turn.

By the end of the day I had grown accustomed to the handling deficits and was hustling the bike around the track at a pretty good pace. When I slowed down to ride the bike’s pace I could enjoy its pleasing ergonomics, good fueling and powerful brakes. With some minor chassis revisions and some suspension tuning it will be a nice track day companion or great street going sportbike.

The best looking, best running, best handling Harley custom ever made.

When the white flag (in this case a T-shirt) ended my time on the bike, I faced ninety miles of Interstate by rental car to my next macchiato. The obligatory Chicago traffic gave me ample time to reflect on the bike and the Roehr motorcycle company.

When I first heard about the project the business model that came to mind was Aprilia. Sourced engines, suspension, brakes, wheels combined with their frame and bodywork. Aprilia has it easy since they are located in Northern Italy where one can subcontract for an entire motorcycle (including castings) in a week and a half.

Roehrich must have seen the Harley / MV Agusta merger coming years ago.

After reflection I realized that the Roehr is far more American than Aprilia. Roehrich is not following in the footsteps of Ivano Beggio, he is following the American tradition of a custom bike builder. Use a Harley engine, make a frame, give it attitude and make it unique. When I let go of my “racetrack performance above all else” prejudice and thought about the bike as an American Custom I realized that the Roehr was, quite possibly, the coolest and most bad ass Harley ever built. It would flat stomp any of that cable TV, iron cross junk on a curvy road. Race track quibbling aside (which, granted, is what I am paid to do) the Roehr looks sexy, sounds great, is comfortable to ride and is quicker than most twins. It is also just about the most exclusive streetbike you can buy. From that frame of reference the whole endeavor makes a lot more sense.